Last summer, sea surface temperatures around Florida reached the highest levels on record—close to 97 degrees Fahrenheit in some areas—according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

As Philip Gravinese, Ph.D., assistant professor of marine science at Eckerd College, documented last summer when he and five of his students conducted research at the Mote Marine Laboratory in the Florida Keys for two months, those elevated temperatures wreaked havoc on dozens of marine species, including the one in his ongoing Florida stone crab experiment. He noticed more female crabs rejecting their eggs, and the larval survival was lower than in the previous summer’s research. This summer, NOAA is predicting more hot water.

But Gravinese and his students aren’t waiting for that to happen.

In his Ecophysiology lab underneath the Galbraith Marine Science Laboratory on the Eckerd campus are two tanks holding 18 Florida stone crabs collected from neighboring Boca Ciega Bay. The crabs are being tested to see how they are affected by varying levels of elevated temperatures. All of the crabs are adult females, in part to help standardize the testing and also to identify how thermal stress may impact future egg production.

These aren’t just crustaceans. The Florida stone crab industry generates more than $30 million a year in revenue. And 99% of the stone crab claws harvested in the United States come from Florida.

“In response to last summer’s heat wave, we started a physiology study on stone crabs across a range of temperatures,” Gravinese explains. “This work is ongoing and is being led by my first-time research students Gillian Smith and Jonathan Ballard.

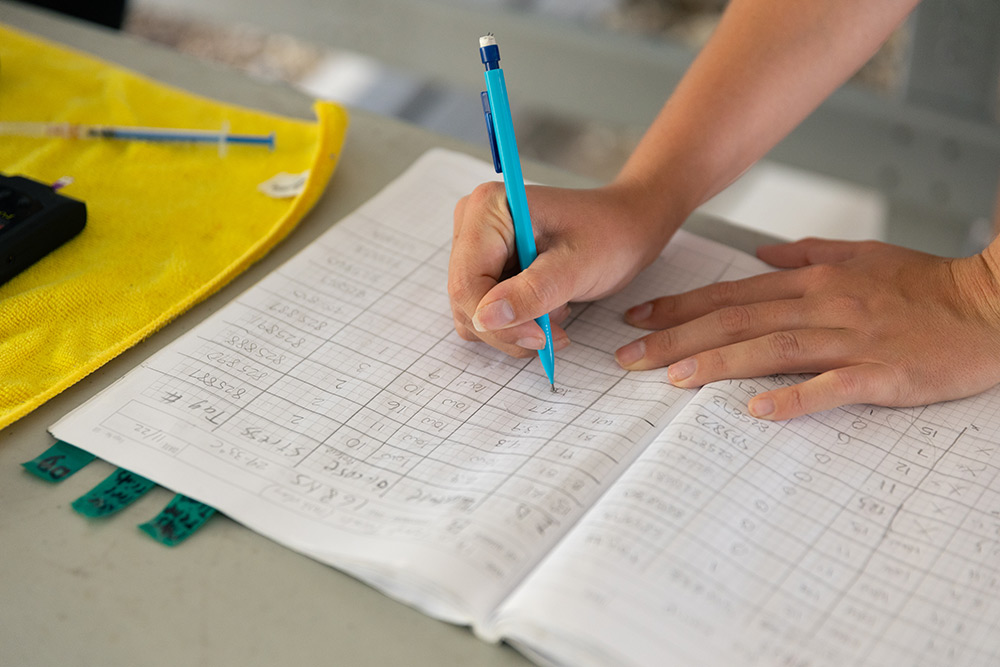

“We are testing the crabs at 24, 27, 30, 33 and 36 degrees Celsius [75 to 97 degrees Fahrenheit]. We are slowly ramping temperature at a consistent rate using digital thermostats in our Ecophysiology Lab. The crabs are being held at each temperature for about a week. We are measuring their stress, lactate levels, protein serum levels, and doing respirometry [metabolism/measure of O2 consumption] at each temperature.”

So far, Gravinese says, all of the crabs have survived, but as water temperatures climb and corresponding oxygen levels drop, the animals struggle. “Imagine an Olympic athlete that may train at altitude with less oxygen to condition their body,” he adds. “Warmer water holds less oxygen. The difference here is that the crabs are not training, but rather trying to physiologically cope and survive.” The final results are publishable, making the findings available to organizations such as the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and Florida’s Stone Crab Advisory Panel. “We will also be back in the Keys this summer with at least four Eckerd students continuing and adding to the larval work we did last summer.”

Everyone knows climate change is a problem, says Jonathan, a junior marine science student from Pearland, Texas. “The water temperature has shown a steady increase over the years. But a lot of species, including stone crabs, don’t have the ability to regulate their body temperature. So we’re trying to see how greatly stone crabs are affected. Can they withstand those projections? And if so, at what cost?

Junior Jonathan Ballard and first-year Gillian Smith

“We want to bring that data forward,” he adds, “so it serves as a guide for crab fishers to determine what can be done to prevent this. People don’t like to pay 45 to 50 dollars a pound for stone crab claws right now, but it’s going to be increasingly harder to fish for them. Hopefully, we’re giving crab fishers reason to find a solution before it’s too late.”

Jonathan is a transfer student from Houston Community College who is finishing his first year at Eckerd. “There are not many promising results for where we’re headed,” he admits. “We’re trying to see if the crabs are resilient at all. The answer so far is no. Most of the data shows that any animal subjected to these stressors does not do well.”

Gillian, a first-year marine science student from Indianola, Iowa, is here because she took a special marine science course during high school. “For a first-year student, doing research like this is a great opportunity,” she says. “It’s special because it’s so hands-on. And seeing how this research is done is going to help me run my own research project.

“And I’m worried,” she adds, “because I care about the environment.”