They huddle over wooden boxes like surgeons at an operating table. Wires must be soldered. Circuit boards, switches and microcomputers must be correctly positioned.

Spring Semester is coming to a close, and the half-dozen Eckerd College students in Michael Hilton’s Engineering a STEM Exhibit class are racing to complete their projects before classes end.

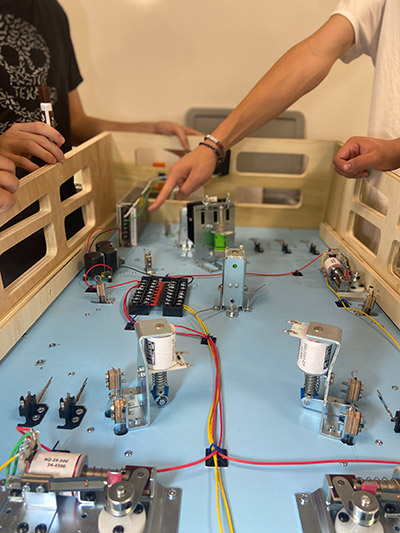

They’re building functional pinball machines. With spring-loaded launchers; working flippers; and lighted, strategically placed bumpers. The students work in teams to make three machines. When the semester ends, each $1,500 machine will be disassembled and many of the parts reused.

Mike Hilton, Ph.D., an assistant professor of computer science at Eckerd who spent 22 years as a research scientist at Procter & Gamble, says that although this is the first time he’s had students construct working pinball machines, he knew the games are referred to as “a STEM course in a box” because he had built one himself.

“And they really are,” he adds. “I also thought building a pinball machine would be fun,” he adds. “It’s at the outer limits of what the kids [all first- and second-year students] are capable of.”

Professor Hilton (back right, in blue) teaches students how to construct their electronic pinball machines.

Before he got started, Hilton not only spent nearly a year piecing together a machine of his own that students could study in class, he arranged a field trip. Hilton, Physics Shop Supervisor Paul Fratiello and the students toured the Replay Amusement Museum in Tarpon Springs, home to more than 100 working pinball machines and video games. “The staff at the museum opened up some of the machines, so we could see exactly what features were inside,” Hilton says. “Then we came back to Eckerd, and the students drew up their own designs.”

The game that’s played today is far removed from early versions. Pinball evolved in Western Europe in the 18th century, borrowing from games such as bocce and ground billiards. In pinball’s earliest form, players used a cue stick to shoot wooden balls down a narrow table that had holes in the table’s bed. The table included small wooden pins that players could use to divert their ball into a hole.

In 1869, inventor Montague Redgrave began manufacturing tables in Cincinnati, Ohio, that used spring launchers to fire marbles onto the table. But it wasn’t until 1931 that coin-operated “pin games” arrived (five balls for a penny), providing cheap entertainment during the Great Depression. Electricity was added a few years later, and players finally got to be a real part of the game when flippers were added in 1947.

A view of the electronic underbelly of one of the student-constructed pinball machines.

“The class taught me a lot about engineering through small projects and then allowed me to apply it on the beautiful pinball machine creation,” says Guadalupe Obayi, a sophomore mathematics and Spanish student from Miami. “Dr. Hilton is an amazing professor who balances educating and allowing us to have a sort of safe independence. I did not know how much detail hides behind the wooden base of the pinball machine.”

“I have never, never been in any class like this,” adds Jack Wisniewski, a sophomore physics student from Sandwich, Massachusetts.

“I have played with pinball machines before, but the complexity never struck me until I tried to build one. Professor Hilton served as our guinea pig of sorts, building one before our class even started so he can help us.

“We’ve all gotten to the point now where he gives us a list of goals for the day, and we can accomplish those independently. Looking towards the future, I’d like to be more hands on. I think this class has pushed me towards an engineering path. I have really enjoyed this project and hopefully can do something similar in the future.”

Being entertained by the project is something Hilton is already considering. “If the students get finished in time,” he says with a grin, “hopefully we can have a tournament on campus.”