During his Spring Break trip last March to the shark lab at the Bimini Biological Field Station in the Bahamas, William Szelistowski, Ph.D., associate professor of biology and marine science at Eckerd College, told the staff about Qingsong “Seisho” Song and his shark skulls.

Seisho, a sophomore environmental studies student at Eckerd, has been collecting the skulls ever since he discovered a prehistoric megalodon tooth at Bryce Canyon in Utah four years ago. He personally prepares and preserves the skulls, and keeps most of them at Szelistowski’s lab at the Galbraith Marine Science Laboratory, where some are on display.

“The people at the shark lab were very interested in having a couple of the specimens,” Szelistowski says. “So they called him and cut a deal. If Seisho could get to Bimini, they would trade room and board at the lab for a week for two shark skulls. He is unusually talented in the way he preserves them.”

The skulls are mostly those of lemon or hammerhead sharks because, Seisho says, they are iconic species and very common. Seisho works with commercial and recreational fishers both locally and in South Florida to obtain what is usually considered waste. “The skulls are free because the fishermen usually discard the head,” Seisho explains. “So I negotiate with them and salvage the discarded heads for educational purposes.”

After removing any flesh, Seisho uses hydrogen peroxide to bleach the skull.

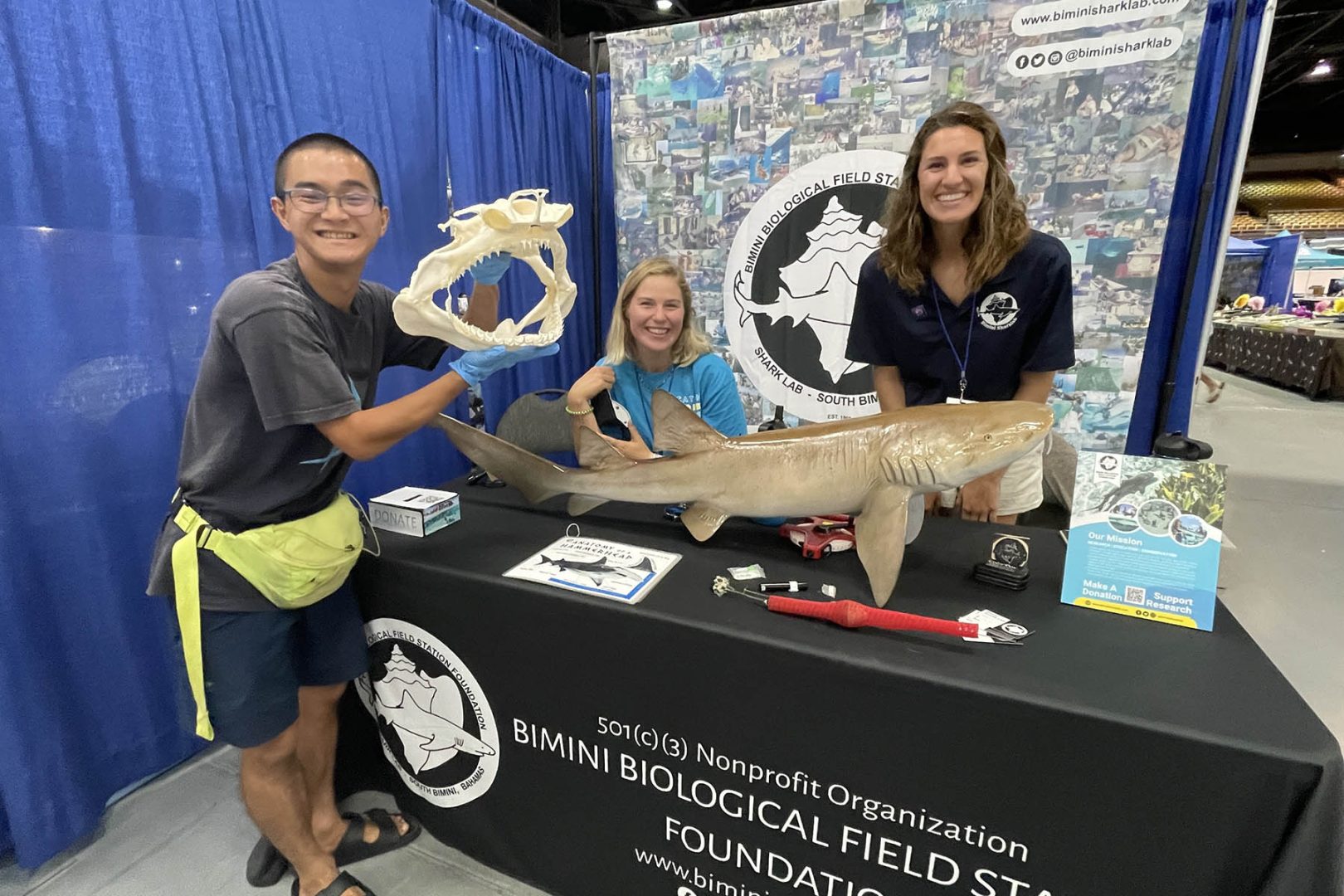

Headed for a thrilling week of #shark study in The Bahamas, Seisho Song '24 #MarineScience @eckerdcollege proudly displays the Great #Hammerhead skull he salvaged from Florida commercial fishermen and manually prepared as an educational donation to @BiminiSharkLab. pic.twitter.com/feFsEeTzTI

— EC Marine Science (@ECMarineScience) August 30, 2022

“On a large great hammerhead shark I have—it’s about 2.5 feet in width—I needed 20 gallons of bleach. Examining the skulls is like trying to solve a mystery that not a lot of people do,” he adds. “The information you obtain—like feeding mechanisms—can be useful for conservation purposes.”

But Seisho and his two skulls still needed to get to Bimini. The problem was solved in June when he learned that SharkCon 2022 would be held at the Florida State Fair in Tampa a month later. And that the Bimini shark lab would have a booth there. Seisho drove to Tampa, donated the skulls, and in August, he flew to Bimini for a week.

“The skulls that Seisho prepared for us will be a valuable contribution to our education and outreach efforts, both in Florida and beyond,” says Matthew Smukall, president and CEO of the Bimini Biological Field Station Foundation. “These skulls allow students and members of the public to better understand the intricate anatomy of the species, and hopefully thereby improve their appreciation for these important predators.”

Seisho’s hometown is Urayasu, on Tokyo Bay in Japan. His father is a businessman, his mother is a flower artist, and for fun, Seisho—what else—goes fishing, usually here on campus or from the Sunshine Skyway Fishing Pier. “And I’m also a big fan of seafood,” he adds. “I’ve tried a lot of maniac fish species like pinfish, Spanish mackerel, pigfish … I can’t remember all of them.”

How many skulls has he collected? “I cannot count,” he answers. “I know I have done at least 35 species. My dream job,” he adds, “is to be a specimen curator at a museum. Recently I had a chance to talk to a curator at the American Museum of Natural History, and the career included traveling around the world finding so many different exotic species to bring back to collections.

“It also included documenting data, permits for transporting specimens around the world, and educating the public about evolutionary differences through specimens. That was when I knew that this is exactly the job I have been looking for.”

Seisho enjoys his time with small sharks in the Bahamas. Photo courtesy Bimini Biological Field Station