Science is a little closer to restoring coral reef systems—paramount to ocean biodiversity and preventing coastal erosion—thanks to the findings of a four-year study jointly conducted by the University of Southern California and Eckerd College.

A paper titled “Evidence for adaptive morphological plasticity in the Caribbean coral, Acropora cervicornis” was recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, according to Eckerd co-author Associate Professor of Marine Science and Biology Cory Krediet, Ph.D. It is the result of four years of fieldwork in the Florida Keys with the help of Mote Marine Laboratory.

Researchers planted 10 different genotypes across nine different reef environments to determine if certain corals would do better in certain reef conditions, Krediet explains.

“It’s like matching the landscaping with the climate and the type of soil. You want to match the coral to the environment,” he says.

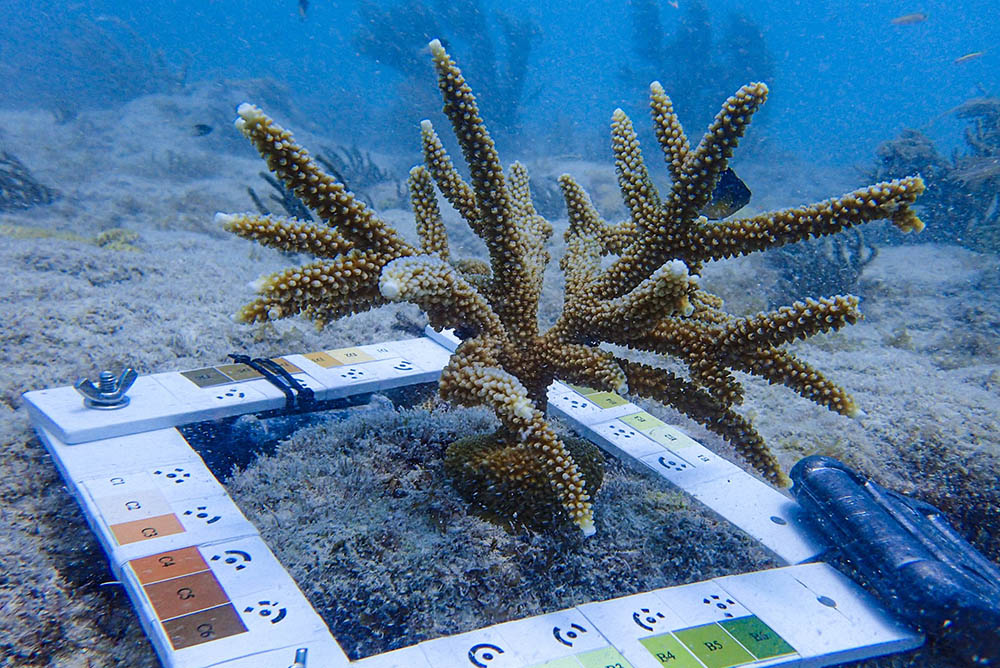

Certain genotypes of Caribbean coral can grow well in differing conditions. Photo credit Erich Bartels

Once the corals were planted, Wyatt C. Million, Maria Ruggeri, Sibelle O’Donnell, Erich Bartels, Trinity Conn, Krediet and USC’s Gabilan Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences Carly Kenkel, Ph.D., monitored the growth, health and mortality of each coral species on each reef for three years.

Science diver SCUBA teams took photographs in order to create 3D models of the planted corals to accurately measure their growth and hardiness over time. Krediet says Eckerd students assisted with the data collection and processing on the boat and in the lab at Mote for each trip.

Throughout the study, researchers discovered that the Caribbean coral Acropora cervicornis is phenotypically plastic—meaning that certain genotypes can grow well in differing conditions, including water temperatures and light concentrations. “Because of the plasticity observed,” Krediet notes, “future restoration projects may be able to target certain coral genotypes for outplanting at specific reef sites.”

Krediet says now that work on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration grant project has concluded, he and his students will continue studying corals to identify bacteria that can act as probiotics to help improve the resilience of existing reefs. Work is already underway in his campus laboratory, and the next step will be to introduce the bacteria to corals in contained aquarium environments at the Mote Marine Laboratory in Summerland Key, Florida.

“We just applied for some funding that we will find out about early next semester,” Krediet says. “We’ve already identified some candidate microbes with our anemone system, and the next step will be to introduce those to some corals and record the interactions.”