It seemed everyone knew that Eckerd College could be home to some Indigenous history, but no one could quite place it, says Anna Guengerich, Ph.D., an assistant professor of anthropology there.

“It was really fascinating to me that clearly there is a lot of memory in the common consciousness and that people were aware that there are potential traces of Native American history on campus,” she says. “No one had the definitive answers. There wasn’t a lot of hard evidence.”

People would talk about finding remnants of shell mounds around Fox Pond and near Wireman Chapel, but not much more. Intrigued, Guengerich set out to answer the first question in archaeology: Where were these sites actually located?

Eckerd’s 188-acre campus was partially constructed with filled land—an area of soil added to an existing shoreline to extend the habitable area into a body of water. To figure out where traces of the past might lie, Guengerich enlisted the help of Aidan Thomas, a senior anthropology student from Danville, Virginia. The duo scoured resources both digital and archival to create a map of where Eckerd College’s original shoreline ends.

Assistant Professor of Anthropology Anna Guengerich

“I took Professor Guengerich’s Archaeology of the Southeast U.S. class, and when I was done reading about the native mounds, I became very interested in the mounds at Maximo Point,” Aidan says. “It made me curious about whether Indigenous people actually lived on the campus, and my fascination just kept growing from there.”

After hitting a number of dead ends, Guengerich finally heard about the Land Boundary Information System from a colleague and was able to find aerial images of Eckerd from 1943—nearly 15 years before the filled land was brought in to begin campus construction. She imported the images into the ArcGIS mapping software and overlaid them on a current satellite image of campus.

Aidan relied on the Eckerd College library and campus archives to view architectural notes that indicated where old native mounds would have been and other landmarks of the original shoreline. College Archivist Cathy McCoy ’71 helped find original documents and plans preserved to document Eckerd’s history.

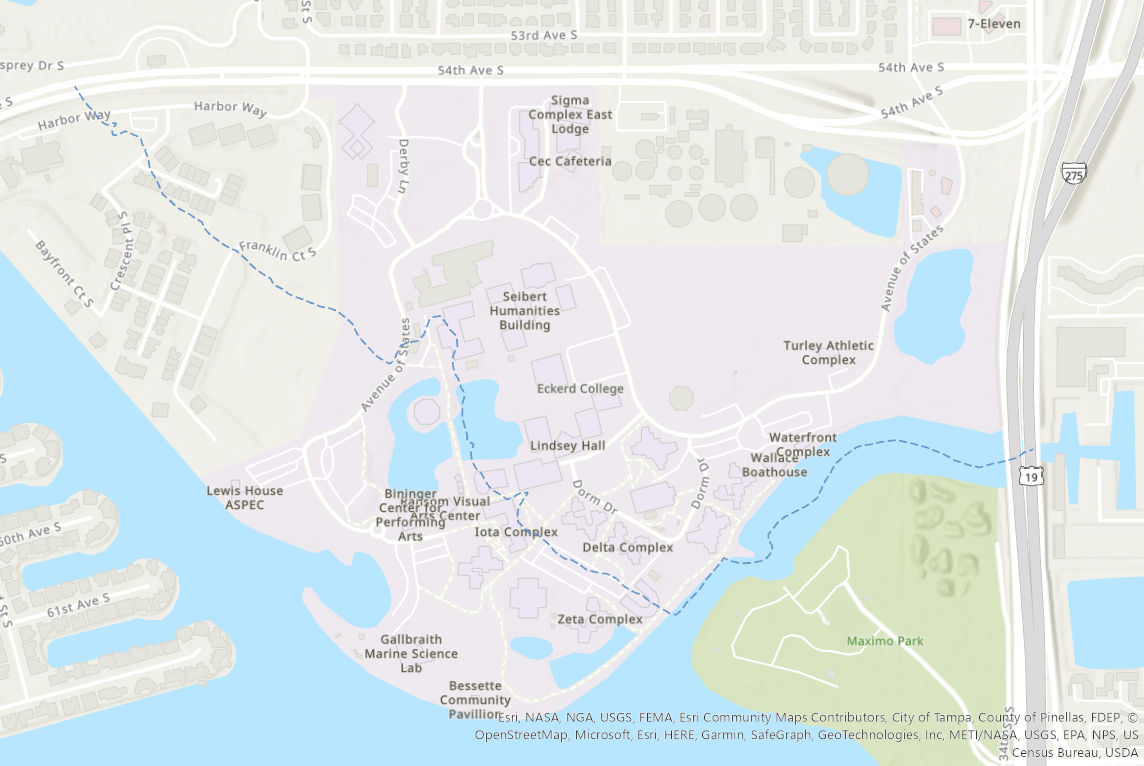

A sample of the digital map showing Eckerd’s original shoreline (dotted line)

The finished product—a digital map—confirms that several buildings south of the Palm Hammock Nature Area were built on filled land—including the Wireman Chapel; Nielsen Center for Visual Arts; Galbraith Marine Science Laboratory; and Iota, Zeta, Omega and Nu residence halls. In fact, the original shoreline extended farther into Frenchman’s Creek than our current seawall to the east.

Guengerich says having this map is just the first step toward creating something special at Eckerd. Her natural science colleagues could use the boundaries to study the ecological differences between the soil and other resources on the natural land versus the vegetation on the fill that has been around for roughly 60 years. Also, if an Indigenous group with local ties supports it, she’d like to see on-campus excavations for artifacts to be preserved and restored to the communities that created them.

“It’s a very long-term goal that would only proceed if we worked hand in hand with Native American communities who want it done,” she says.

The possibility of campus excavations excites Aidan because not every student has the ability to travel abroad to go to their first dig.

“I grew up with Indiana Jones and Lara Croft and always knew I wanted to go into archaeology,” Aidan says. “My focus has always been on the classical Mediterranean, but being able to study the history of the places where I am will better prepare me for graduate school.”

In the past year, a campus movement toward more Indigenous involvement has taken hold, starting with the formation of a student organization, Coalition of Students from Indigenous Action, and the creation and approval of a campuswide Land Acknowledgment recognized by the Seminole Tribe of Florida.

With the addition of the campus map, Guengerich sees the forward momentum pushing students, faculty and staff to become more mindful that they were not the first people to inhabit this space and to treat the privilege with humility.

“It’s come together like lightning, really,” she explains. “Everyone involved with COSIA really sees the value in diversity and the visibility of diversity on campus. Our native connection is just one of many strands of our diverse campus community to celebrate.”

Aidan thinks, more practically, that if students become more aware of the origins and fate of those who came before them, they’ll be more respectful and better stewards of the campus.

“I really do think creating that connectivity will protect the campus,” she adds, “from an ecological standpoint.”