“A sudden marine heat wave off the coast of Florida has surprised scientists and sent water temperatures soaring to unprecedented highs, threatening one of the most severe coral bleaching events the state has ever seen.” CNN headline, July 16, 2023

Cory Krediet, Ph.D., associate professor of marine science and biology at Eckerd College, had seen the warning signs and anticipated what was coming. But even he was surprised at how fast and how early it was unfolding.

Coral and dinoflagellate algae are an example of one of nature’s most successful symbiotic relationships. They depend on each other to survive, Krediet explains, but if stressed by increased ocean temperatures or pollution, the coral will expel the algae. Without the algae, the coral loses its major food source and its color, leaving the coral eerily bleached and vulnerable to disease, starvation and death.

Within the last several months, sea surface temperatures around Florida have reached the highest levels on record—close to 97 degrees Fahrenheit in some areas around the Keys—according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The warming isn’t just extreme—it’s happening much earlier than normal. Water temperatures around Florida don’t usually peak until late August and September.

This is no small problem. Not only do Florida’s reefs generate billions of dollars through activities such as fishing and tourism, Krediet says more than 25% of marine species depend on coral reefs at some point in their lives. A NOAA study published last year found that climate-change-fueled coral disease and bleaching had already reduced Florida’s reefs by 70%.

“Coral reefs are essential to the ocean ecosystem,” Krediet adds. “We have the potential to devastate the marine environment. It’s up to us to take action now.”

This is exactly what Krediet and his students are doing. He has been working in his lab on campus to try to expose different types of algae to temperature variations and see which is more resilient.

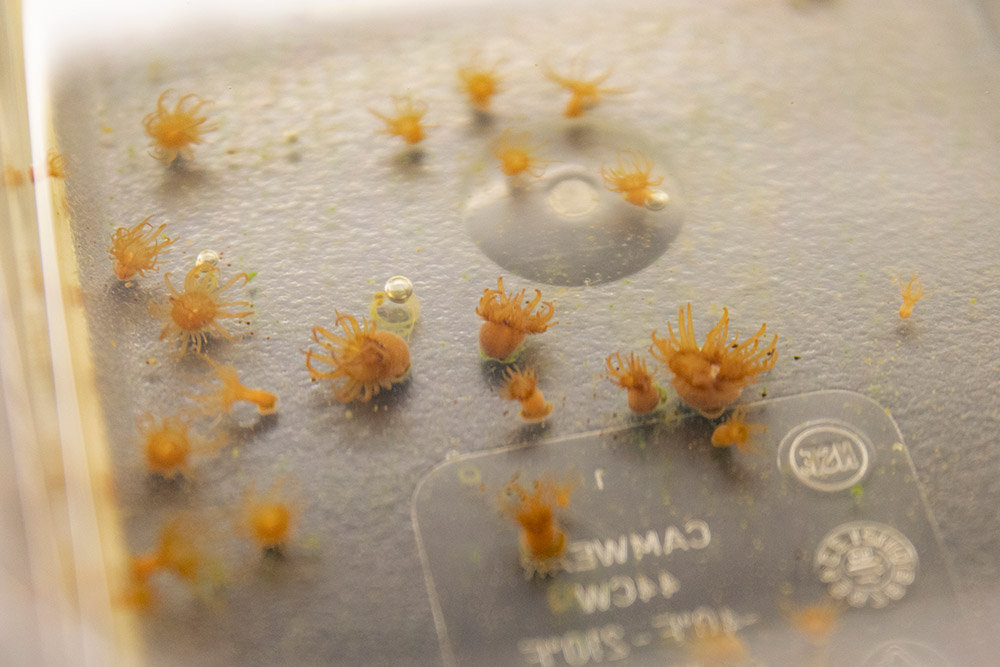

Anemone polyps in the lab at Eckerd College; photo by Cory Krediet

“We can mimic what’s going on in the Caribbean right now,” he says. “We’re trying to introduce beneficial microbes to corals that don’t already have them, to improve their resilience and enable them to handle stress a little better.”

Working alongside him are senior marine science students Cara DeLacluyse, from Grayslake, Illinois, and Victoire Litre, from Harrison, New York. “My research focuses on how acclimation to environmental stressors, such as high salinity, improves pathogenic resistance in anemones,” Cara points out. “Corals currently face many compounding stressors, one of which is disease. Any tool we can use to possibly improve their survival is worth studying.”

“It feels like a race against the clock,” Krediet adds. “All the work we’re doing needs to happen faster. It’s not just the water getting warmer. The oceans are also acidifying, and that also increases the risk of coral disease and makes them more vulnerable. So it’s this one-two punch of stressors that can be too much for the coral to handle.

“Our job is to gather data and present it so that the public, and the people in power, can make the right decisions. It’s not too late. But it’s a global problem; no one country can solve this.”

Stone crab; photo by Philip Gravinese

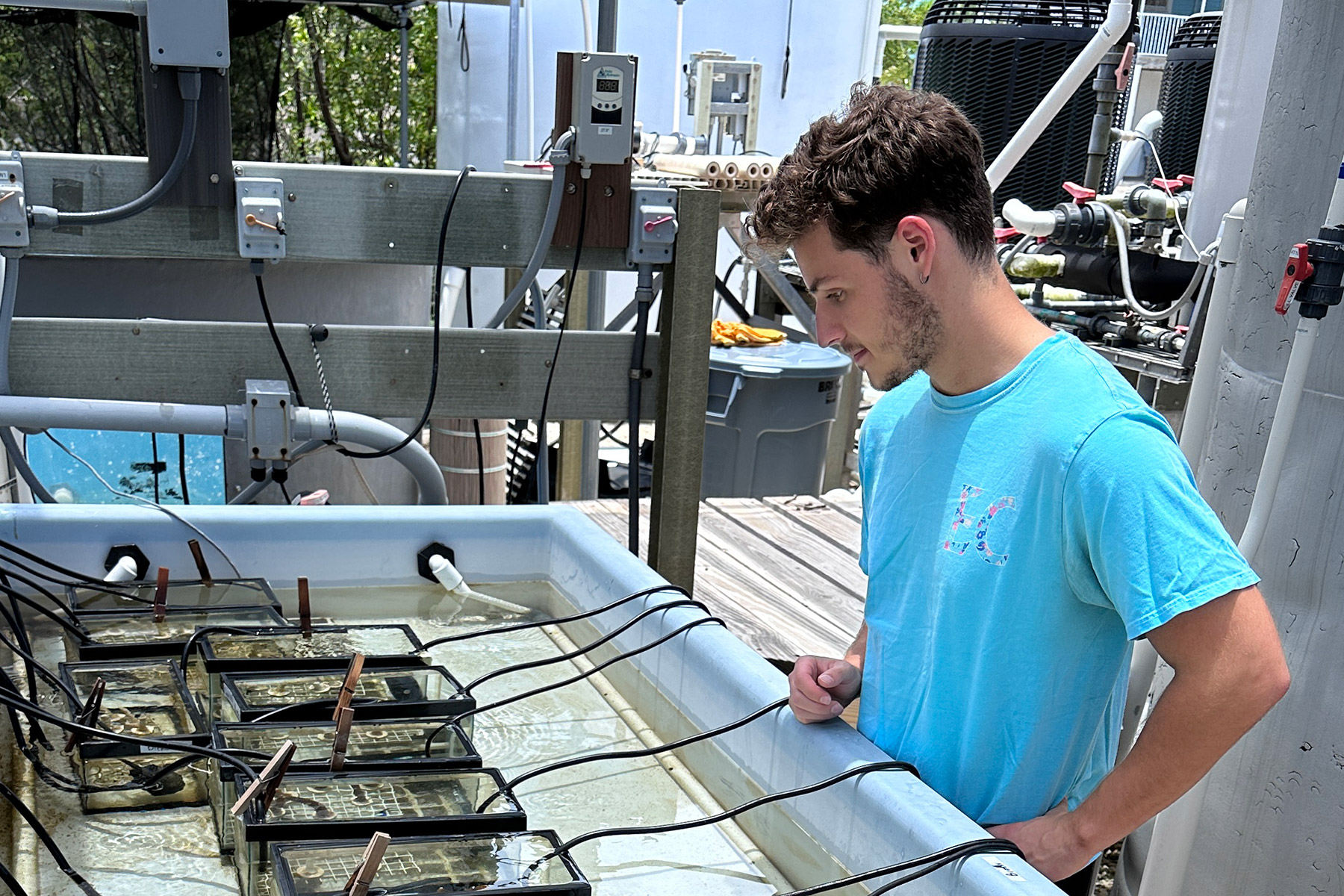

Krediet and another of his students, Connor Dempsey, a senior marine science major from Babylon, New York, will be spending several weeks in late July and early August at the Mote Marine Laboratory’s Elizabeth Moore International Center for Coral Reef Research & Restoration in the Florida Keys. Along with a fully equipped marine science laboratory, the center has dormitories; a field support staff; and easy access to reefs, sea-grass meadows and mangrove forests.

They aren’t the only representatives of Eckerd College at the center working to save marine life. Philip Gravinese, Ph.D., assistant professor of marine science at Eckerd, also is conducting research at the Mote Marine Lab this summer along with four of his students. Using a grant from the National Science Foundation and a collaboration with Louisiana State University, Gravinese and his team are studying the stone crab fishery—a multimillion-dollar industry in Florida.

Gravinese and his collaborators at LSU hypothesize that future climate change could result in stone crabs moving north or into deeper waters, and stone crab populations in Florida may be susceptible to community fragmentation.

“We are collecting stone crabs and raising their larvae in present day, mid-century and end-of-century temperature and pH conditions” Gravinese explains. “The goal is to identify what the larval-crab swimming behaviors are under ambient conditions and then see if those swimming behaviors change when they grow up in the different climate scenarios.

“The swimming behavior data we collect will then be used by colleagues at LSU to create the first population model for the stone crab fishery that incorporates how the population may become fragmented with future climate change. The hope is that this model will inform managers of how the population may shift with climate change.”

Gravinese adds that students working on this research also gain outreach experience as they present their work to middle school and high school students. The students also will be invited to contribute as co-authors when the research is compiled for publication.

“Dr. Krediet and I are excited to provide opportunities for our students to work on answering important and novel research questions,” Gravinese says, “which is a perfect example of Eckerd’s dedication and commitment to hands-on research experiences.”

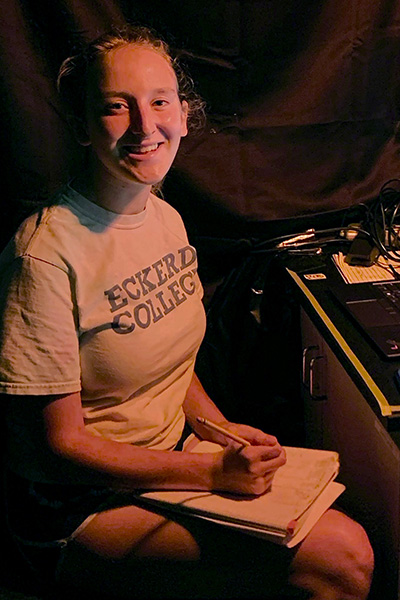

Top to bottom: Seniors studying stone crabs in the Florida Keys include Rebecca Meberg, Eliza Patty and Thomas White