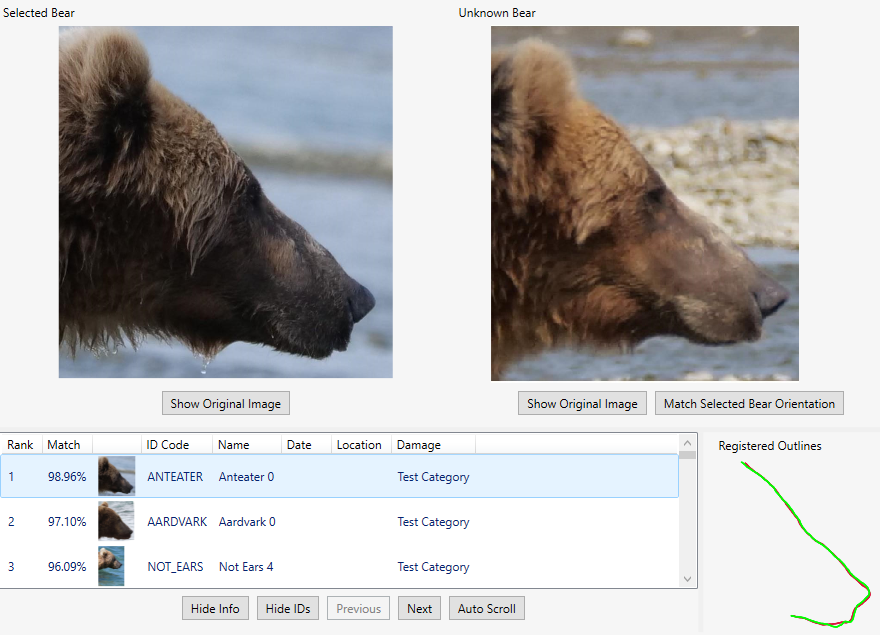

A screenshot from the software developed at Eckerd College that is used in research on marine mammals, sharks and, most recently, Alaskan brown bears.

Computer science and the study of wildlife may seem like unlikely partners, but scratch the surface and you’ll find a powerful relationship that increasingly benefits everyone involved.

That collaboration is on full display at Eckerd College, where two computer science professors are helping to make animal research quicker, easier and more precise. Kelly Debure, Ph.D., professor of computer science, is the driving force behind software used in research on marine mammals and, most recently, Alaskan brown bears.

And Mike Hilton, Ph.D., assistant professor of computer science, has developed software used in research on gopher tortoises and frogs. He has released it as an open source, so other wildlife researchers can work with him.

Over the past 20 years, Debure has supervised scores of Eckerd students who have maintained and enhanced DARWIN (Digital Analysis and Recognition of Whale Images on a Network). That software, initially implemented under the direction of former Eckerd faculty member John Stewman, has been downloaded thousands of times. It is designed to help researchers identify bottlenose dolphins, but it also has been used by research groups on spinner dolphins, fin whales, basking sharks and other related species.

Nicks and notches along the edge of a dolphin’s dorsal fin, along with scratches and other markings that an animal acquires, are features that can be used to uniquely identify an individual dolphin, Debure says. DARWIN uses the edge markings to compare the dorsal fin outlines for similarity.

The software can help wildlife scientists do something vital to their research—identify individual animals. Debure says researchers who are monitoring certain animal species need to identify specific individuals in order to perform tasks such as making population estimates, determining home ranges and modeling association patterns.

Professor of Computer Science Kelly Debure

Assistant Professor of Computer Science Michael Hilton

Dolphins breaching in Boca Ciega Bay just off the Eckerd College campus. Dorsal fin markings help researchers identify individuals. Photo taken under the authority of NMFS LOC No. 15512.

Using cameras that can take thousands of pictures has the downside of needing to process a mountain of data. This is where computer science comes in, Debure says. Using the DARWIN software, biologists can cull and process the information in a reasonable amount of time.

Debure is currently working with Alaska-based wildlife researcher Beth Rosenberg to study a congregation of brown bears using the DARWIN software to recognize individual profiles to help identify each bear.

And once again, Debure’s former and current Eckerd students are involved. During the early part of the pandemic, Adam Russell ’01 took on the rewrite of the baseline software, and Rachel Halepeska ’21 conducted software testing. Leo Okiti, a senior mathematics and computer science student from Dubai, United Arab Emirates, is currently working on modifications to the user interface as well as the assessment of performance metrics.

The research is not a one-way street; computer scientists also gain from the collaboration. “It’s wonderful,” Debure says, “because we gain access to a large collection of image data to analyze and to hone the software.”

The animal Mike Hilton focuses on is slightly smaller. Before he came to Eckerd in 2018, he worked as a research scientist for Procter & Gamble for 22 years and served in the Air Force for four years, exiting as a captain. He has taught computer science at the University of South Carolina and, along with several colleagues, has been awarded four patents.

“When I got to Eckerd, I realized it’s a very animal place,” he says. “So I thought, What kind of a problem is interesting to me that involves animals? So much is going on with artificial intelligence, such as facial recognition for humans. Could I do something similar for animals?”

Gopher tortoises have unique patterns on their carapaces that are used by Eckerd faculty and student researchers in a local preserve. Photo: Bill Hawthorne ’21

He soon found himself at nearby Boyd Hill Nature Preserve, along with Jeff Goessling, Ph.D., assistant professor of biology at Eckerd. “Jeff has been doing research out there for five years,” Hilton says. “When I told him what I was interested in, he said, ‘I’ve got the perfect animal for you.’ Gopher tortoises have patterns on their carapace [the top part of the shell], which are unique and humans can learn to identify. A machine might be able to do that.”

So Hilton went to Boyd Hill and mounted a camera over the entrance to a gopher tortoise burrow. “They spend most of their time underground; they have one entrance; and when outside, they spend a lot of their time outside near the entrance, sunning or socializing,” he says. “It’s really an ideal location to try to capture images that can identify tortoises.”

As with Debure, Eckerd students have been, and continue to be, involved in every step of the work, Hilton says. “Junior Leah Knezevich and senior Jane Downer helped with the data collection at Boyd Hill and the analysis of the time-lapse videos. Mark Yamane is doing his senior thesis on creating a machine learning algorithm to identify specific tortoises. And sophomore PK Patel is helping me develop a human-in-the-loop continuous learning system to improve automatic tortoise detection in the videos.”

Hilton and his team now have 24 cameras mounted over burrows that take 250,000 photos a day. “That’s 375 gigabytes of data every day,” he says. “It’s a massive amount of data you have to process and store. You also have to organize the results and do a statistical or network analysis. That’s what makes it a hard problem and why this work is unique.

“The goal?” he asks. “Why are we bothering? Mostly because of habitat loss, gopher tortoises are an endangered species. We’re trying to conserve and protect them. These creatures live to be 60 years old or more, and we’re trying to understand what their social structure is. How do they decide who they like or don’t like and how does it affect their reproductive success?”

Yes, Hilton adds, it is unusual to have computer scientists working with field biologists. “But they [the biologists] are just dying to have the computer people there,” he says. “Collaboration between computer science and wildlife research is not new.

“But it’s a unique aspect of Eckerd College. We have a unique perspective on how computer science can be used to benefit the natural world, and we offer opportunities to make a difference to the planet.”