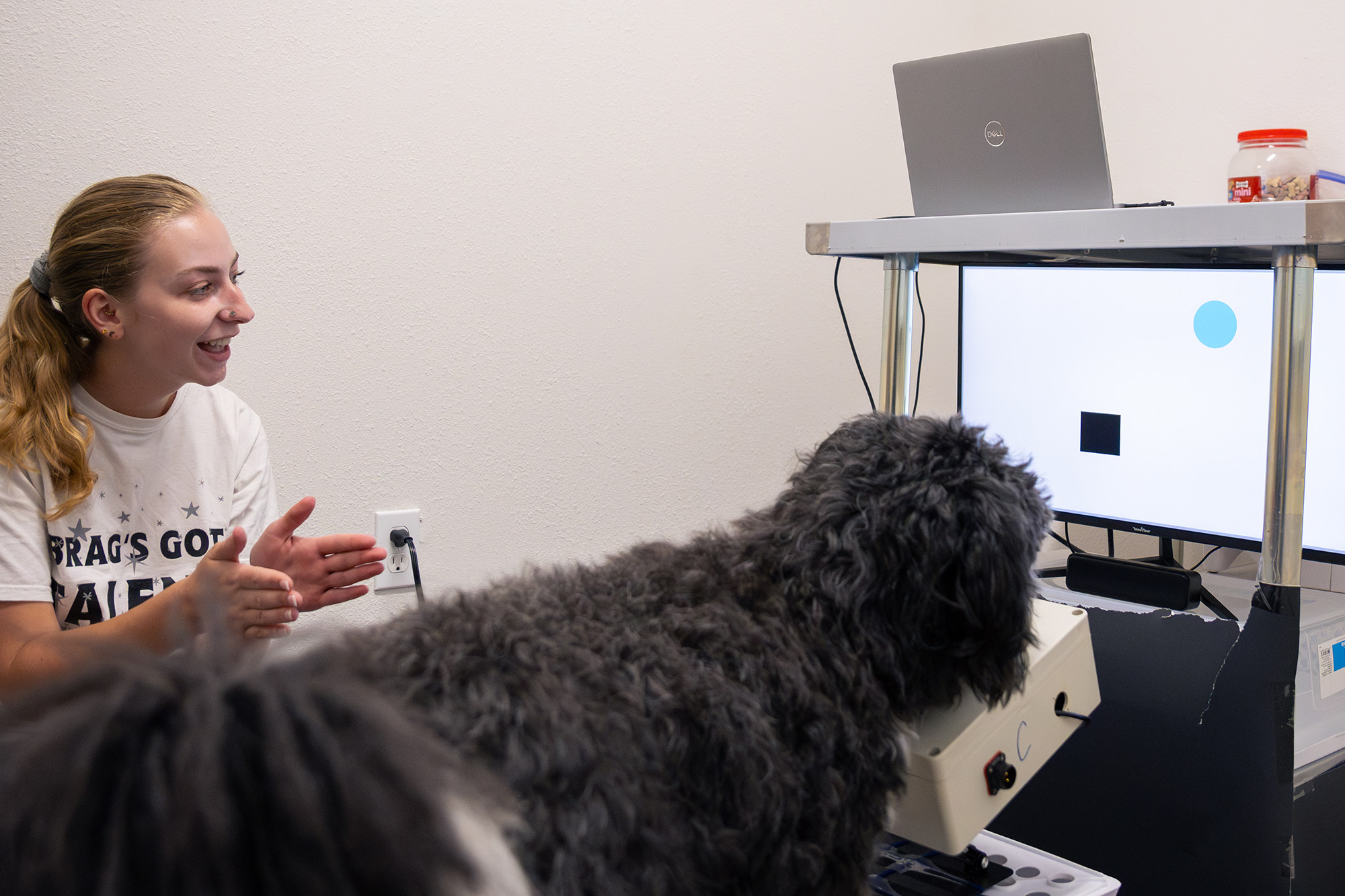

In a lab at Eckerd College, Orlo the rescue pup stares at a screen before choosing which direction he wants to click on the controller buttons with his nose. A right choice will end in a delicious treat, so he’s careful.

This activity—playing a video game—is part of a study led by Allison Kenawell, a senior animal studies and biology student from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Psychology and Animal Studies Professor Lauren Highfill, Ph.D. Orlo has been introduced to a gaming console and controls a cursor on a computer game interface. The game involves pressing four directional buttons to move a big blue dot to make contact with a black square on the screen.

“It’s been great to work with Orlo. He is such a smart dog,” Allison says. “He knows he gets to play his game whenever he sees me.”

Since July, Orlo has played the game 47 times with a total screen time of 12 hours. At each progressive level, the black square gets harder to reach. To advance, he must move the blue dot to the black square in a certain time constraint, and he must press the directional buttons fewer than seven times. These requirements must be met twice consecutively to pass the level. Orlo is currently on level six, the final level, and if he can pass, he will be considered successful by the standards of the study.

The project is one of a few supported by the Belgya Family Engaged Learning Endowed Fund. Established in 2021 by Mark and Beverly Belgya, parents of Eckerd marine science graduate Karli Belgya ’22, the fund provides perpetual support for students of any major to experience hands-on learning through research, service learning or internships.

Visiting Assistant Professor of Animal Studies and Psychology Sarah Nadler ’10 adopted Orlo to serve as a therapy dog. (He’s still in training.) The estimated 2-year-old dog plays an active role in Nadler’s psychotherapy and counseling services located in downtown St. Petersburg, Florida.

According to Nadler, therapy dogs work with clinical professionals to improve physical, social, emotional and cognitive functions in humans. They can work in both individual and group settings, which makes them different from service dogs—those trained in specific tasks to help a single person. Therapy dogs also are different from emotional support animals that are meant to provide companionship within a home.

In addition to meeting with clients, Orlo recently learned how to play video games. This research was first conducted with sea lions by Kelley Winship, Ph.D., a scientist working for the National Marine Mammal Foundation. She conducted research with three adult California sea lions, introducing them to this computer system and developing training protocols, which Orlo follows now. He is the first dog to use the system.

Orlo practices his video game for about 20 minutes twice a week. He usually takes a break as part of a trainer-led reset. This keeps him from getting bored or frustrated. More recently, researchers have noticed that when Orlo is struggling with the game, he’ll walk away briefly as if performing his own reset. He generally stays focused on the task and displays excitement when he completes a level.

“He is capable of figuring it out on his own,” Allison says.

After he was rescued, Orlo suffered from general and separation anxiety, and Nadler’s primary goal was to rehabilitate him and teach him to cope with these big feelings. Enrichment is one way to do that because it provides mental and physical stimulation. If Orlo can pass level six and prove that canines are fully capable of learning to play video games, this kind of enrichment may be an option for the millions of American households that own dogs. Video games could be a way to keep dogs entertained while owners are away.

All three of Winship’s sea lions became successful after 18 months of playing the game; Orlo is nearly there after nine months.

“I could not have asked for a better dog to start this study,” Allison says with a smile.

Soon he may fully master the art of video gaming—changing the lives of dogs across America.