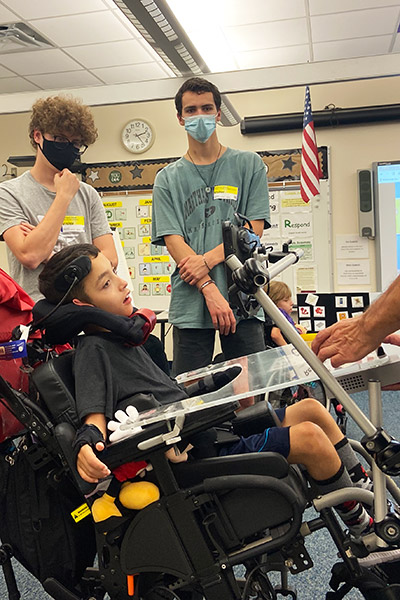

Jackson Butler ’25 (left), Noah Kazansky ’25 (second from right) and Physics Shop Supervisor Paul Fratiello (far right) try various ways to mount a motion-activated speaker onto the tray of Cristiano Taboas-Gonzalez, a third grader at the Nina Harris Exceptional Student Education Center. Photos: Michel Fougères

Cristiano Taboas-Gonzalez stares intently at the little metal box attached to the tray in front of him. “You can do this. You can reach it,” whispers someone in the group from Eckerd College.

If Cristiano can pass his hand over the box, he will activate the tiny sensor inside, and a recorded message will play. He also can ask for help or for something he needs. He slowly lifts his right arm and aims it at the target.

Cristiano has an intellectual and a physical disability—he uses a wheelchair and has limited ability within his hands and arms, and with his head. He is 9 years old and a third grader in Angela Fitzpatrick’s access classroom at the Nina Harris Exceptional Student Education Center in Pinellas Park. Nina Harris is a K–12 public Title I school that serves about 220 students with significant cognitive disabilities. Students also often have physical disabilities, language impairments, behavioral disorders and other developmental disabilities.

About 85% of the students do not have sustainable verbal skills to communicate or self-advocate, 40% or more come from households at or below the poverty level, and about 20% live in foster care.

This is testing day. Eckerd College Physics Shop Supervisor Paul Fratiello and three Engineering a STEM Exhibit students from the College are visiting Nina Harris to try to find the best way to position the box—a motion-activated speaker—so Cristiano can use it. “We can’t do this over the phone,” Fratiello says. “Every child has different abilities, so we need to test each one individually and in person.”

Cristiano makes several attempts, grunting with effort, but he can’t get close enough. “Maybe if we tried mounting the box on an angle,” offers Noah Kazansky, a first-year physics student at Eckerd from Bronx, New York. Fratiello likes the idea. “We’ll go back to Eckerd, make the adjustments we need to, and come back and try it again,” he says.

Sam Schmidt Hansen, a first-year Eckerd student from Arlington, Virginia, is standing next to Cristiano.

“It feels really good to be part of a project where we can see a real-world impact,” Sam says. “It’s very eye-opening how some people really rely on technology.”

This is the special relationship Eckerd College has with the Nina Harris Education Center. The motion-activated speaker, designed and built by Michael Hilton, Ph.D., assistant professor of computer science at Eckerd, with help from several Eckerd students, is the latest collaborative project between the schools.

Credit the Cleveland Browns for bringing them together.

Four years ago, Fratiello, who has a mechanical engineering degree from Purdue University and has taught physics in high school, went to Quaker Steak & Lube® in Clearwater to watch a Browns game with a friend visiting from Cleveland. The local Browns Backers fan club’s philanthropic project was raising funds for Nina Harris, and they had recently funded the purchase of a 3D printer. At halftime that day, Jacquie Grimes, a behavior specialist from Nina Harris, gave a presentation on the school’s plan to utilize the printer. When Grimes finished, Fratiello handed her his business card. “I might be able to help you,” he said.

Fratiello, Hilton and Eckerd students have been helping the school ever since.

Jessie Brown, curriculum technology specialist at Nina Harris, contacted Fratiello for assistance with designing parts to make with the 3D printer. And later, she called him (and the Eckerd STEM class) for help making a glue-stick holder for one of her students.

Jessie Brown confers with Paul Fratiello outside the Nina Harris building in Pinellas Park.

“I didn’t know who to turn to,” Brown says. “I tried reaching out to three local high school STEM programs and clubs to help us, but it never went anywhere. Then Paul came along. He was at the right place at the right time, thank goodness.”

But back to the project at hand. There are devices, Brown says, that play recorded messages for disabled students. But they sometimes require the student to press a button, or they are affected by changes in the lighting. And they typically cost several hundred dollars. The one Hilton made cost about $60.

“Jessie contacted us this year and said they have a student with a specific need,” Hilton says. “She said they have a device, but it doesn’t work very well, and she asked if there is anything we can do that will work better? After that, we were off to the races.”

Hilton says he was already familiar with gesture sensors and infrared devices to measure proximity, like you’d find in a paper-towel dispenser in a restroom. “Once we found a sensor we thought might work,” he says, “Eckerd students started to build out other parts for the recording and the power supply.”

Brown tried out the box on three Nina Harris students and was favorably impressed. But some students, like Cristiano, struggled with it. “So Paul and I and several of our students have discussed different modifications,” says Hilton.

First-years Noah Kazansky (left) and Sam Schmidt Hansen ponder how to mount the speaker.

“I was thinking of adding two sensors to increase the range,” adds Noah. “We’ve got to fix that.”

That sense of obligation is not lost on Hilton. “Accessibility issues for these kids are enormous,” he says. “A school like Nina Harris does not have the resources to engage with professional engineers to build the kind of devices they need. It’s not financially feasible. So to have students able to work on something like this is really a remarkable thing.

“Each one of the children has such a unique and specific need, so even if we can help just one child a year, that’s something that couldn’t happen without the kind of collaboration we have with Nina Harris.”

Hilton and Fratiello agree that helping design and build devices that make life and learning easier for disabled students is the main goal for the Eckerd students. “But there’s also an important lesson for them,” Brown adds, “and it happens here at Nina Harris. They [Eckerd students] see that not everyone is like them, and that there’s nothing scary about being around children who are so significantly impacted by their disabilities.

“And then later,” she adds with a smile, “when the Eckerd students are working for Microsoft or Apple or someone else, they’ll remember the importance of accessibility.”