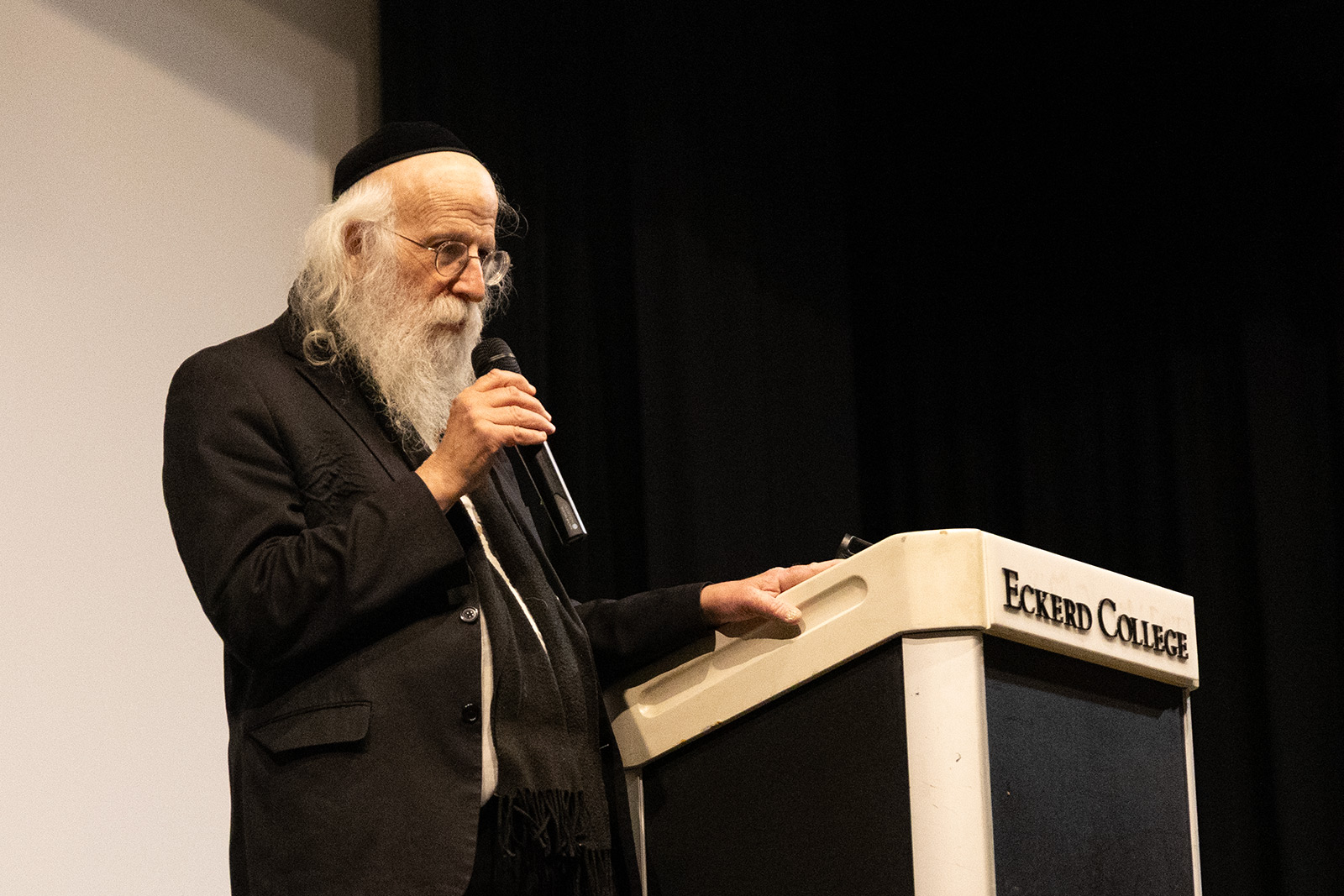

“It’s been so invigorating to be here year after year, both with him and without him,” says Avraham “Alan” Rosen, Ph.D., referring to Dr. Elie Wiesel.

Wiesel was an author, human rights activist and Holocaust survivor, and he served as a visiting Winter Term professor at Eckerd College for more than 20 years before dying in 2016 at the age of 87.

“But without him is not really without him. There’s a sense of his presence,” Rosen adds, pointing out Carolyn Johnston, Ph.D., sitting in the front of the audience. She co-taught a course with Wiesel for 24 years and had a meaningful friendship with him. Johnston is Eckerd’s professor of American studies and history, as well as the Elie Wiesel Professor of Humane Letters.

She and a gathering of students aren’t the only ones to listen to Rosen’s lecture on a recent Tuesday evening in the Dan and Mary Miller Auditorium. Peter Armacost, Eckerd’s president from 1977–2000; his wife, Mary-Linda Armacost; and President Jim Annarelli—all with Ph.D.s—are also in attendance.

Rosen was educated in Boston under the direction of Wiesel and visited Eckerd last March to explore the enduring nature of the 92NY lectures—Wiesel’s longest running teaching forum—which rarely focused on the Holocaust. 92NY is the 92nd Street Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association in New York, which has aimed to bring people together and offer programs in performing and visual arts, literature and culture, education, talks, health and fitness, and Jewish life for over 150 years. Wiesel called 92NY “a kind of second home” and “a sort of yeshiva,” a place of Jewish learning, according to its website.

Rosen recently became the director of publishing and coordinator of archives at the Elie Wiesel Foundation, and he serves as the Project Scholar of The Elie Wiesel Living Archive at the 92NY.

Now living in Jerusalem with his wife, children and grandchildren, Rosen emphasizes the importance of traveling to Eckerd to share stories about his past experiences with Wiesel.

“My trip here was special,” he says. “On both flights [from Jerusalem], I was the first passenger on the plane.”

He jokingly says maybe it’s because he “looks like a rabbi” or because he’s an older Jewish man, “but there’s a lot of old Jewish men there,” he adds, as laughter fills the room.

The real reason he was on both flights first was because he was coming to Eckerd, he says, even if the flight crew didn’t know.

In Jewish tradition, you cannot simply leave Jerusalem—you must have compelling reasons, he says. By our gathering together, Wiesel’s presence is brought out and felt more boldly, Rosen explains, which made his trip a compelling reason to leave Jerusalem.

Throughout his lecture, titled Bringing People Together: The Visionary Call of Elie Wiesel’s 92NY Lectures, Rosen details Wiesel’s approach to teaching and his legacy that carries on. Rosen urges the audience to visit The Elie Wiesel Living Archive, where you can listen to Wiesel’s lectures over the years on anti-Semitism, Jewish holidays and observances, and more.

After his lecture, Rosen opens the floor for questions from the audience. Mary-Linda Armacost thanks him for the illuminating presentation and asks what Wiesel’s strongest impact was on Rosen.

He describes a few of his experiences, including the dedication to knowledge Wiesel displayed in his classroom.

“He slept very little,” Rosen adds, “maybe five hours at the most, and he read constantly, and he learned constantly. He learned [every] moment [of] every day.”

Students ask if Rosen has a favorite memory with Wiesel and if there’s a correlation between suffering and wisdom or profound teaching. Professor of Literature and Comparative Literature Jared Stark, Ph.D., asks about the most important parts of being a teacher and a student.

Rosen answers that Wiesel asked more from students. He pushed them. Wiesel was “speaking to them on a level that, for many, was over their heads. But over their heads in such a way that was believing that they could reach that point.”

Wiesel used most of his time to teach tradition, literature and philosophy, Rosen says, rather than focusing solely on the Holocaust. According to Rosen, Wiesel believed the essence of Jewish identity is not suffering but beauty. So he wasn’t a somber symbol of loss and suffering, but we can remember him as the “master teacher” who was constantly witty and amusing—as well as a father, son and husband.